THE

PROTESTING PRIEST

Frank Cordaro has spent his

life working against the establishment. He’s got a few stories to tell

Words by Angela Ufheil

Photos by Hannah Little

Photos by Hannah Little

Frank Cordaro wants to

make one thing clear. He chose this life.

We’re standing in the

foyer of the Bishop Dingman House, one of four structures that make up the Des

Moines Catholic Worker. A cart filled with plastic-wrapped packages of bread

and bagels takes up space in the already-cramped room, as does a shelf lined with

boxes of cereal. In the kitchen, a team of volunteers is preparing spaghetti

and meatballs. A few dozen members of Des Moines’ homeless population watch the

news, play chess, and chat while waiting for dinner. They’ll take some of those

bagels with them on the way out.

The Catholic Worker

Movement is made up of 240 communities around the world, all united by a

mission to serve the homeless and protest injustice. Frank co-founded the

Des Moines, Iowa chapter in 1976, and he lives and serves the community now. In

the years between, he was a Catholic priest, a non-violent protester, and a

prisoner of the state.

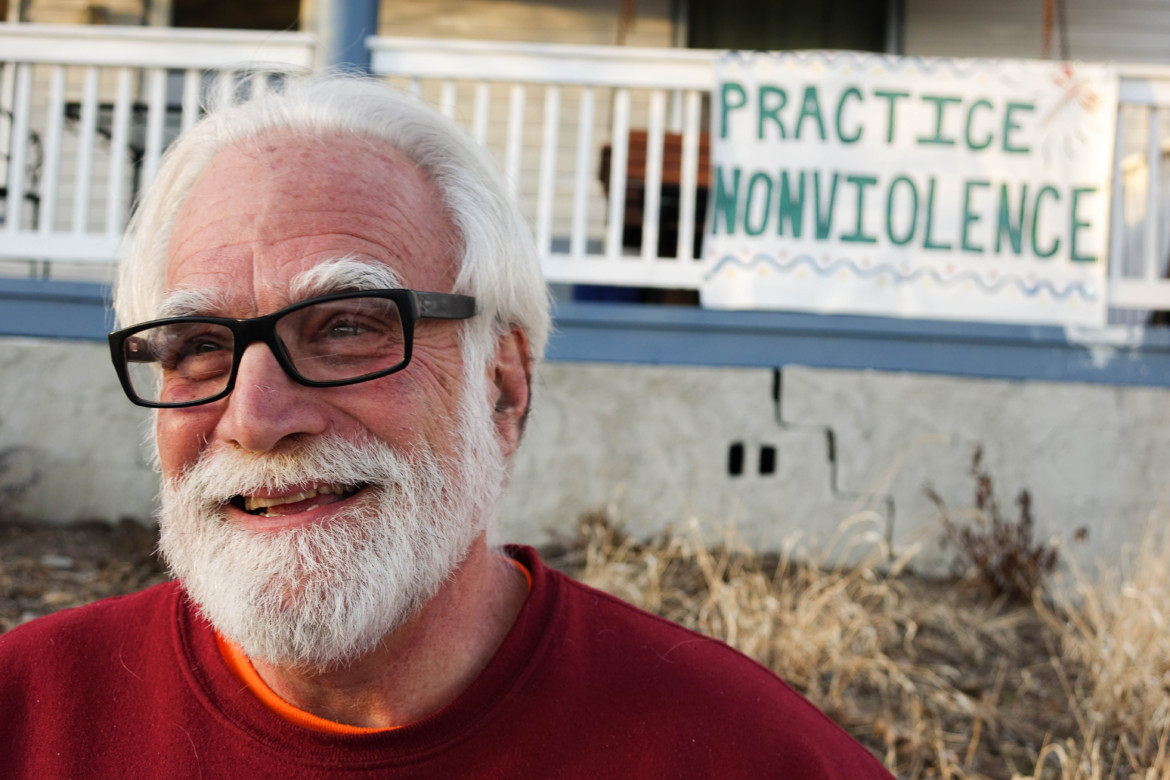

Frank is 66 years old,

with a snowy-white beard and gut that’s probably caused a few kids to wonder

what Santa is doing in Des Moines. He wears black glasses that shift around his

face to accommodate dramatic facial expressions. He gets right in my face and

gestures broadly when he’s making a point. I’ve never once seen him sit still.

He can relate most

anything to the New Testament. He’s chosen poverty to better understand the

people he’s trying to serve. And his controversial protesting methods get

people talking. He’s inspired a lot of the people he works with: “For me, one

of the most significant things about Frank as a person is that he, for many

decades now, has been very committed to struggling for peace and justice,” said

Aaron Jorgenson-Briggs, a resident at the Catholic Worker. “And he has taken on

personal risk and made personal sacrifices to do that.”

He’s also pissed a lot of

people off. “Logic sometimes goes out the window with Frank,” said Bishop

Richard Pates, the current leader of the Des Moines Diocese. “I think he lives

in his own world sometimes.”

Frank won’t confine

himself to one identity. I find myself returning over and over again to Frank’s

favorite description of the Catholic Worker community. “We do heroic and noble

work here,” he said. “We’re not always heroic and noble people. And that’s OK.”

Frank Cordaro standing near the entrance to the Bishop

Dingman House, one of the Catholic Worker Houses in Des Moines. The wall behind

him is decorated with news-clippings of famous protesters.

The True Believer

Frank

doesn’t do anything halfway. “I’ve believed in a lot of things, but

at any given time, I believed in them strongly,” Frank said.

During his childhood in

Des Moines, those strong beliefs had an all-American edge. “If I was anything,

I was a true believer. In America, patriotism, the valor of war and the necessity

of the Vietnam war,” Frank said.

His father, George

Cordaro, was a Marine in World War II and won two Purple Hearts. He enrolled

his daughter and five sons in Catholic school and raised them to be God-fearing

patriots. Like any good, hot-blooded American, Frank got into football. He

captained and played linebacker for the undefeated Dowling Catholic High School

team, and it’s easy to tell that he’s still proud of it. He was inducted into

Dowling’s athletics hall of fame last year, a distinction his father also

claimed.

Frank’s brother, Joe

Cordaro, is two years older than Frank and remembers him as a straight arrow.

“You’d never look at him and predict what he is now,” he said, laughing.

He might be talking about

Frank’s first time getting political. His senior year at Dowling, four

classmates put out an “underground” newspaper criticizing the Vietnam War. “I’m

embarrassed to say it, but I was part of the group that went after these guys

publicly,” Frank said. “I was really blinded.”

Despite, or perhaps

because of, Frank’s fierce beliefs, his classmates gravitated toward him. Joe

said others loved his brother’s sense of humor. Frank’s popularity earned him a

spot on the student government each year. But Joe also remembers that popularity

didn’t blind Frank. “He defended the defenseless and always helped those in

need,” Joe said. “His inside, his heart, really has always been the same.”

He defended the

defenseless and always helped those in need. His inside, his heart, really has

always been the same.”

– Joe Cordaro

Joe thinks that

willingness to help the less fortunate comes from their parents. Both men

remember their mother, Angela, as a giving woman who couldn’t help but root for

the underdog. Their father was the same. George made his sons shovel others’

sidewalks after blizzards and at times literally stopped his car to help people

in need. “He taught us things that go beyond athletics. How to treat people,

how to take care of your neighbor,” Joe said. “I always think in the back of his

mind, he knew he wasn’t going to be around very long.”

George was not a healthy

man. He emerged from the Second World War as a chain smoker, and he had his

first heart attack the day of Frank’s First Communion. Heart problems put him

in the hospital several more times before he passed away during Frank’s senior

year of high school at age 47.

Losing George was painful

for the family. His personality had defined much of their life, and his absence

left Frank searching for a father figure and something new to believe in. Frank

had no idea that he’d already found the former in Maurice John Dingman, who

became bishop of Des Moines in 1968.

George wasn’t far from his

final heart attack when he invited the bishop to dinner. There, Frank and

Bishop Dingman clashed. Frank wanted Dowling Catholic High School moved to a

wealthier part of town. Bishop Dingman said he couldn’t make that change so

quickly. “I used to call him Bishop Ding-a-ling. Thought he couldn’t make a

decision,” Frank said. “I was pretty hard-headed. Later on, I’d die for that

man.”

But Frank had to meet

someone before understanding all the good Bishop Dingman was doing for the

Catholic Church. That someone was a radical named Jesus.

Frank Cordaro in his home at the Catholic Worker in Des Moines,

IA. An Alcoholics Anonymous meeting is hosted there at 5 pm on Fridays.

Finding Jesus

In Matthew 5:39, Jesus

tells his followers, “You have heard that it was said, ‘Eye for eye, and tooth

for tooth.’ But I tell you not to resist an evil person. If someone slaps you

on your right cheek, turn to him the other also.”

It’s the Bible verse where

we get that saying “turn the other cheek.” Most of the time, we say it to

someone who’s been wronged, to encourage them to react to the injury with

forgiveness instead of violence.

Turns out, there’s another

interpretation. Scholars have pointed out that, during Jesus’ time, slapping a

person across the face with the back of the hand was a statement of power. A

member of the upper-class might backhand a lower-class person, or a master

might do the same to a servant or slave.

A punch or open-handed

slap was a whole different story. This kind of strike was seen as a statement

of equality. So if slaves “turned the other cheek” after a backhand strike,

they were demanding their attacker treat them like an equal.

That’s the Jesus whom

Frank discovered while reading the New Testament in college. He attended the

University of Northern Iowa on a football scholarship, and admits that he

didn’t spend much time on his studies. “I didn’t have real respect for

the academics,” he said. “When I left college, I didn’t know how to find a

reference book at the library.”

But it’s clear Frank’s

done some studying since. “I found this new way to read the Bible,” he said. “I

read it as first-century literature. I need to know where, when, why these

things happen. Then I can construct what the author is trying to tell me.

That’s what allows me to make these sweeping statements.”

For Frank, the historical

context makes the message clear. “If you want to walk like Jesus, you gotta act

like Jesus. If you want to act like Jesus, you go to the book and see what he

did,” he said.

Jesus healed the sick and

restored the blind. He told his followers to shed their wealth. And, in Frank’s

interpretation, he pissed the Romans off so much that they had him executed.

That’s where Frank sees the radical Jesus who’s inspired him through his life.

“I’m telling you, he’d be against war in this country,” Frank said. “If you

can’t read that book, any of those Gospels, and come up with that understanding

of who Jesus was, you just can’t read.”

With a new understanding

of the Bible came a new understanding of Bishop Dingman, the man Frank used to

make fun of in high school. These days, Frank raves about the bishop: “I’m

telling you, the guy was extraordinary. Progressive, pro-woman, pro-peace,

pro-Jesus.”

Bishop Dingman became

Frank’s mentor, and inspired him to speak out against the United States’ role

in the nuclear arms race. He was also the one to ordain him as a Catholic

priest.

Before entering the

priesthood, though, Frank had to take care of a few things. He started the Des

Moines chapter of the Catholic Worker. He kept studying the New Testament,

which he said is easy to read, but hard to live. It also appears to have put

him into some unusual situations. Like poised in front of the Pentagon with a

bucket of blood in his hands.

Civil Disobedience

It was 1977 when Frank saw

the painting in the Pentagon. It was hung in a small room being used as a

chapel. In the painting, a young man in a soldier’s uniform was sitting in the

pews. Above the soldier’s head was a quote from Isaiah 6:8. “Then I heard the

voice of the Lord saying, ‘Whom shall I send? And who will go for us?’ And I

said, ‘Here am I. Send me!’”

Steve Jacobs, a Catholic

worker from Columbia, Missouri who was with Frank that day, remembers Frank’s

reaction well. “He was just livid. He kept saying, ‘That is so blasphemous.’”

Jacobs found the painting

blasphemous, too. “It’s a quote from the Old Testament about a young man who

worked in the temple, who acquiesced to be the Lord’s follower,” he said. “They

changed the meaning. They seemed to be using the Scriptures, taking them out of

context to justify the war (in Vietnam).”

Frank almost abandoned the

plan that had been developing all week. “He wanted to go and throw blood at the

painting, because it was so manipulative that they would use the Scriptures in

that way,” Jacobs said. “We had to redirect Frank’s attention toward the bigger

picture.”

The bigger picture, Jacobs

said, was essentially a piece of political street theatre. The performance

planning was done at a faith and resistance retreat held at Jonah House, a

faith-based community in Baltimore, Maryland. A dozen activists stuck needles

into their arms, draining their blood into bags and storing it for the show.

Five giant signs were made, each with one letter: D-E-A-T-H.

“The Pentagon is the place

where military violence is planned,” Jacobs said. “So we were laying that blood

down on the steps and pillars of the Pentagon so the people who were planning

it could see the results of their work.”

After taking the tour of

the Pentagon, the activists grabbed their supplies and approached the

Pentagon’s steps. It was August 9, the anniversary of the U.S. nuclear bombing

of Nagasaki, Japan.

Just as Frank reached the

steps, a familiar figure exited the Pentagon: one of his high school football

coaches, wearing an Air Force officer’s uniform.

The coach would have seen

a very different boy from the one he directed on the football field. “Do you

really know what you’re doing?” he asked.

“Yeah,” Frank said. “I

really do.”

His former coach nodded,

climbed into a waiting car, and was gone. The curtains went up. Frank reached

into his pocket for his packet of blood. He screamed, “The Pentagon is the

temple of death!” and threw the blood at the building.

Frank said being arrested

for the first time under the Pentagon’s pillars was one of the most authentic

experiences of his life. “That’s where real liturgy takes place, in the public

domain. At personal risk,” he said.

During his first trial, he

admitted to the charges, saying life is valuable and must be protected. He

would use a similar argument each time an act of civil disobedience landed him

in front of a judge. All of them put him behind bars for sentences ranging from

30 days to six months.

Somewhere between his

activism and subsequent prison stays, Frank found time to attend St. John’s

Seminary in Collegeville, Minnesota. He was ordained in 1985.

Frank Cordaro arrested while protesting at Camp Dodge in

Johnston, IA. Photo courtesy of Des Moines Catholic Worker.

Holy Contraband

Frank woke up early in

Sarpy County Jail for his morning routine. It was 1990. He climbed out of his

bunk and checked for guards, then grabbed the small toilet paper-wrapped

package he’d hidden. He stuffed it in the top of his sock, just in case. He

didn’t want to risk punishment.

He knelt for his morning

prayers. Frank prayed for the parish he’d left behind. He prayed for the broken

people in prison with him. He prayed for the soul of America. He said “Amen.”

With a furtive glance, he

pulled the package from his sock. Of all the habits he’d developed in prison,

this one soothed his soul the most. He peeled back the toilet paper to reveal a

delicate wafer. He partook in the Eucharist each morning on days when the jail

had no official mass.

Frank doesn’t tell me this

story. When I ask about his time in prison, he gives me a sentence or two

before changing course to conversations about the military-industrial complex

or his theory about the God of Empire and the God of Creation.

No, the holy contraband

story comes from a letter written to his parish on June 17, 1990. He sends me

more than 60 documents via email, each a series of letters written between 1988

and 2014. Volunteers typed them up and printed them in his church’s bulletin,

so his parish could keep tabs on their jailbird priest.

Frank sees jail as a

chance to lead a more disciplined life. He writes, prays and reads more

consistently, spends more time studying the bible. “In jail, I can be selfish

and take care of my own personal, spiritual needs,” he said. “On the other

hand, it’s in the middle of an environment that’s absolute chaos all the time.”

His letters reflect that

chaos, and some sadness, too. Sadness for the broken people the prison system

takes in and spits out. “Almost all the men here were victims first of

broken homes and dysfunctional families before they started breaking laws,” he

wrote in 1990. “The relationship between dysfunctional families, drug and

alcohol abuse and poverty and the people who occupy this jail is almost

absolute.”

Those broken people sought

Frank out when they learned of his priesthood. “They were really ready to talk

to anybody who represented somebody with a listening ear and a connection with

faith,” he said. “Jail was an honorable place to be for a Catholic priest.”

Jail was an honorable

place to be for a Catholic priest.”

– Frank Cordaro

Not everybody agreed with

him, including his own family. “It was hard for me to understand what he was

doing and why he was doing it,” Joe said. “Our mother was not convinced really

quickly, either. She was just angry with him for a really long time.”

Criticism

was harsh. The Catholic Mirror, the newspaper of the Diocese

of Des Moines, printed a letter to the editor in 1992. “How does he find time

to organize these protests when he has a full-time job?” the writer asked.

“What do we tell our children and grandchildren, or how do we explain to them

that this person knows what he does is illegal and against the law, yet

continues to do it anyway?”

Bishop Pates puts it a bit

more delicately. “Everybody has their own methodology. He certainly has

protested strongly for the poor, against nuclear weapons,” Pates said. “You

know, he’s arrested, and he spends a lot of time in jail. I think it’s a

lifestyle that he’s chosen. He feels it’s effective. But there are other ways

of protesting.”

Frank said his

parishioners wished he would have found other ways of protesting, too. “They

didn’t want to see me go to jail,” Franks said. “But on the other hand, I’d

say, ‘OK. Let’s get someone else in this Diocese.’ And they would say, ‘no,

stay.’ So I might have been crazy and quirky, but they liked me..”

Frank calls his time

working under Bishop Dingman a “Camelot moment” for the Catholic Church. The

two of them planned protests together, like trespassing at the Offutt Air Force

Base in Sarpy County, Nebraska. Frank said the bishop even planned to cross the

line himself, an act that might have gotten him arrested.

But Dingman suffered a

stroke right before the action in 1986. He passed away in 1992 without getting

a chance to participate in a protest. Frank, determined to carry out his

mentor’s legacy, wrote the bishops in the area: “The deal between Dingman and I

was that we’d develop a model of priestly life that involved civil disobedience

and resistance. I’m trusting we can carry on in that way.”

And they did, at least for

a bit. But Frank started stirring up other issues, too. “I was very publicly

advocating for women’s ordination,” he said. “I went to demonstrations down at

the cathedral, wearing my collar and everything. I was clearly pushing

boundaries.”

The Church pushed back.

They didn’t want him to protest anymore, at least not in ways that landed him

in jail. So Frank walked away.

Phil, named for the peace activist Philip Berrigan, hangs

out in Frank’s house.

Blood, Hammers and the

B-52

Each year, the Andrews Air

Force Base hosts an open house. Thousands visit the Maryland base to see the

latest in aircraft technology. Pilots perform aerial stunts. Soldiers give

talks. And in 1998, five activists, known as the Gods of Metal Plowshares Five,

attacked a military bomber.

An interpretation of Roman

Catholicism allows for the destruction of property in the name of pacifism.

That’s where the Plowshares movement came from. The movement aligned with

Frank’s goals perfectly. When the first Plowshares action took place in 1980 —

a group of eight damaged a nuclear warhead and poured blood onto documents and

files — Frank knew he’d one day participate. Most Plowshares protests involved

active resistance to war. In this case, active resistance isn’t just writing

letters and making a few calls. It means trespassing on military property. It

means pouring blood. It means breaking things.

Frank wanted to break

things. He’d lost Bishop Dingman. His relationship with the church was tenuous.

His mother had just been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. “I was just kind of

overwhelmed, emotionally,” he said.

He attacked a

nuclear-capable B-52 bomber with another priest, two nuns and a grandmother.

They struck the metal body with hammers and poured their own blood on its

surface. Somehow, even after punching holes in the bomber, they had enough time

to hand out explanatory pamphlets to the onlookers. Then, they were arrested.

Frank wore his clergy’s collar the entire time.

Frank and a fellow protester attack a B-52 bomber at the

Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland. He received a six month sentence for the

action. Photo courtesy of Des Moines Catholic Worker.

“I went through all the

emotions,” he said. “I like acting out things like that. I enjoyed it. It was

exhilarating. It was truth-speaking. It was ground-leveling, spiritual stuff.”

The resulting six months

in jail were not so enjoyable. But Frank said prison was bearable because he’s

proud of what he did to get there. His time in prison is a reflection of his

conscience.

After six months in

prison, Frank returned to the priesthood one last time. A heart attack — a

revelation, of sorts — in 2001 convinced him it was time to leave the order for

good. This final departure was different than simply walking away in

frustration, though. He met the bishop face-to-face. ““Bishop, this has nothing

to do with you, and everything to do with me,” Frank said.

When I ask him why he

left, he’s blunt about the personal nature of the decision. “I couldn’t deal

with the whole celibacy thing,” he said. “I just got tired of the lack of

integrity from myself. I live one life in public, and another in my private

life.”

Today, Frank lives full

time at the Catholic Worker. The main house is named for Bishop Dingman. He has

two cats, Philip and Daniel Berrigan, both named for radical Christian

anarchists, and a girlfriend he says is “half my age, twice my spirit.”

Now, nearly his entire

family supports his protesting. Joe said he got on board when Frank explained

that everything he did was rooted in the Bible. “Jesus was crucified for what

he believed. And Frank thinks we should do the same,” Joe said. “That message

hits people really hard because they’ve always believed the Gospel, but they’ve

never met anybody who really, actually lives it. It’s unbelievable how, every

time Frank goes to jail, these discussions come out of it.”

Before her death, even

Angela Cordaro came around to civil disobedience. “Yeah, she was a co-defendant

at one point,” Frank said. “I told the judge, ‘Hey, you can’t blame me, my

mother told me to do it.’”

Frank and his mother, Angela Cordaro, protesting at the

Offutt Air Force Base in 1989. Frank would later be arrested while still

wearing his clergyman’s collar. Photo courtesy of Des Moines Catholic Worker.

A Fragile Nobility

Frank’s been trying to fit

exercise into his schedule since his heart attack. I tag along for a walk that

doubles as a tour of his neighborhood. His old high school is twenty minutes

from the Catholic Worker houses, and he points out the field where he used to

play football. At times, he gets so involved with his storytelling that his

stride slows to a shuffle, then a stop. After a few minutes of standing in the

middle of the sidewalk, he makes his point, looks around as if just coming to,

and continues marching.

We pass by a group sitting

near the Bishop Dingman House. One woman is holding her arm and crying. Frank

approaches her and they talk for a few moments, voices low. Frank tells her to

take care of herself, and we walk again. I ask if she’s OK.

“No, she’s not OK,” he

said. “This is crazy. She can’t live on the streets like this. She’s a very

strong woman, but she’s just — she needs to get off the street, or die. She’s

been on the street too long.”

I’m not sure what to say.

I observe that coming to the Catholic Worker and having steady meals must be

good for her. “Yeah, when we don’t have to kick her out,” he says.

Frank protects the woman’s

privacy, so I don’t get much more of her story. He does tell me that guests

aren’t supposed to come to the house drunk. Frank usually lets that rule go.

“Everybody comes in drunk,” he said. However, anyone getting too rowdy or

violent has to leave. Kicking out the people who, in his eyes, need the most

help is the worst part of Frank’s job. But he takes the bad with the good.

“That’s just the way it is. It’s still good. It’s just that good isn’t pretty

all the time. Pretty much any good that’s worth a damn is never pretty.”

Frank Cordaro is trying to

do heroic and noble work. He’s not always a heroic and noble person. And maybe

that’s OK.

--

No comments:

Post a Comment