Sep182015

NYT Plays Up Risks to Bomber Pilots, Downplays the Civilians They Kill

New York Times photo of Navy pilots returning

from bombing Iraq. (photo: Adam Ferguson/NYT)

Trying to

wring some melodrama out of the not particularly dangerous lives of US bomber

pilots, the New York

Times‘ Helene Cooper starts off an article with an anecdote

about two US Navy jets taking off from an aircraft carrier on a bombing mission

in Iraq:

In one of the

fighter jets was Navy Lt. Michael Smallwood, 28, call sign Bones, and in the

other was his friend and roommate, Navy Lt. Nick Smith, also 28, call sign Yip

Yip.

For a minute

or two that day in May, the Hornets were right next to each other in the sky,

but then Lieutenant Smith’s plane had engine trouble and began to lose

altitude. Over the radio, Lieutenant Smallwood could hear his friend turn

around, try to land back on the carrier and then eject into the Persian Gulf.

The $60 million Hornet crashed into the sea.

Lieutenant

Smallwood found himself fighting to keep his mind off the fate of his friend,

but his orders were to continue climbing and fly on to Iraq.

Midway through

the article–whose main point, according to the headline, is that “For US

Pilots, the Real War on ISIS Is a Far Cry From Top Gun“–Cooper teases readers again:

As Lieutenant

Smallwood’s plane flew toward Iraq in May after his friend had ejected from his

own jet, he could hear from the chatter on the radio that a recovery effort was

underway. But Lieutenant

Smallwood knew

better than to clog up the frequency asking if Lieutenant Smith and his weapons

officer on the plane had been found alive.

Five more

hours to go. Arriving in the skies over Iraq, Lieutenant Smallwood’s Super

Hornet connected with a refueling tanker to get gas, then continued with the

task at hand. But whenever there was a lull in the flight, “all I could think

about was my roommate and his W.S.O.,” Lieutenant Smallwood said, using the

military term for weapons officer.

At the end of

the article, Cooper finally reveals the information withheld from her initial

anecdote: Spoiler alert! The pilot who ejected was fine. She ends with a quote

from his roommate:

“But I still

had to run down to the room to see for myself,” Lieutenant Smallwood recalled.

“First thing I did was hug him.”

This cozy

ending to Cooper’s drawn-out tale was not altogether surprising, given the low

casualty rate for US military personnel in what the Pentagon refers to as

Operation Inherent Resolve: The Navy has lost only two people in a year of

combat, both in non-combat related injuries, one of which involved falling off

a balcony while on leave (Air

Force Times, 8/24/15)

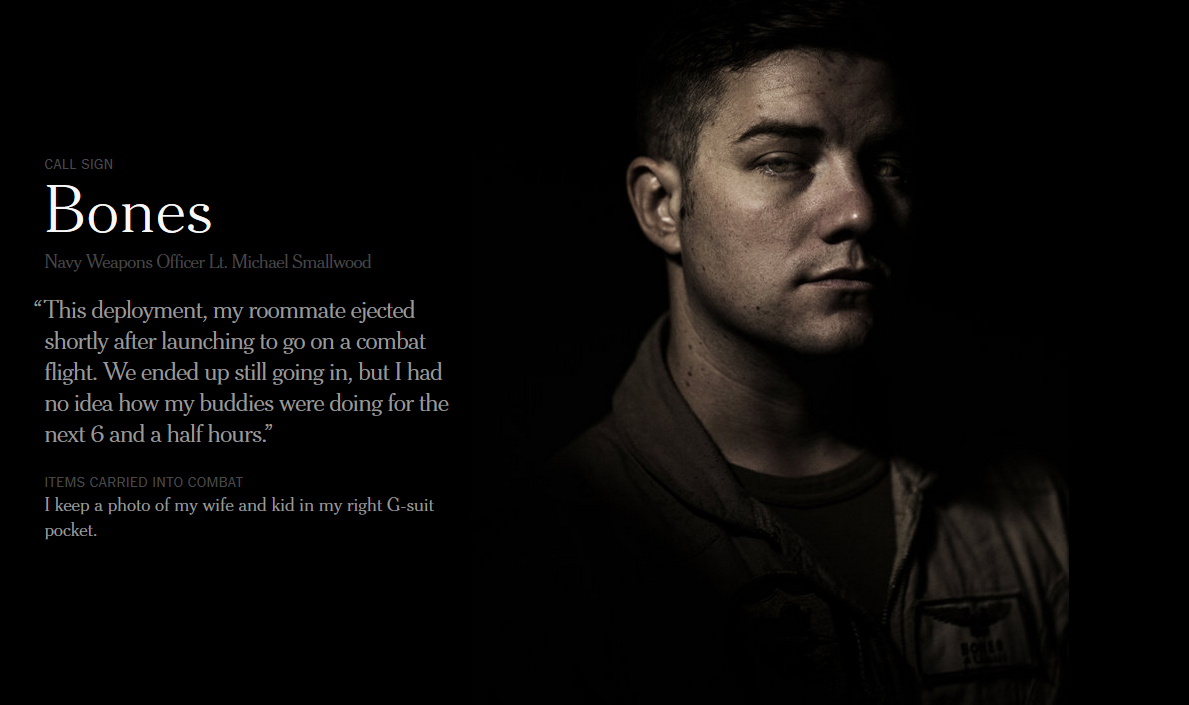

The Times article

is accompanied by a photo gallery of bomber flyers, including Lt. Michael

“Bones” Smallwood, whose tale of a time he was worried dominates the piece.

(photo: Adam Ferguson/NYT)

Cooper does

her best nevertheless to make the reader empathize with the risks faced by

bomber pilots, despite a former flyer’s admission that “if you stay above

10,000 feet, you’re not going to be hit.” Though the mechanical difficulties

faced by Yip Yip dominate the story, Cooper asserts that “engine troubles are

not the only risk at 25,000 feet.” What else is there? Well, there’s

acceleration: “The F/A-18s today require more G-forces than the planes of

the Top Gun era,

and pilots today pull nine Gs instead of four and five Gs”—so pilots have to

make sure they are “not dehydrated or hungover from drinking and crooning the

Righteous Brothers to Kelly McGillis at a bar the night before.”

For comparison

purposes, riders on the Shock Wave roller coaster at Six Flags Over Texas

experience 6Gs six Gs–placing the

amusement park-goers somewhere between Maverick and Bones on the toughness

scale.

There’s one

other risk “beyond that” that Cooper presents the bomber pilots as facing, though

they’re not actually the ones facing it:

Despite the

precautions the pilots say they take, there are civilian casualties from

airstrikes, although the number is in deep dispute. Officials with United

States Central Command, which oversees American military operations in the

Middle East, recently said that they had received reports of 31 episodes

involving civilian casualties since the airstrikes began, and had dismissed 17

as not credible, with six still under investigation. One report, investigated for

more than six months, led Centcom officials to conclude that two children were

probably killed by a coalition airstrike.

That paragraph

is followed by a one-sentence paragraph: “Monitoring groups say the command’s

figures are a gross understatement.” But that’s the last we hear from these

monitoring groups; instead Cooper goes back to a Navy officer, who assures us

that “in the war against the Islamic State, bombs hit their intended targets

almost all of the time,” because “world opinion swings very violently against

you when you start killing the wrong people.”

Cooper also

tells us that flyers “spend a lot of their time in the air watching patterns of

civilian life, to determine whether a movement on a road just outside of Ramadi

is a truck full of Islamic State fighters or a pickup with civilians,” and that

“they very often return to the Roosevelt [aircraft

carrier] with all of their bombs still strapped to the planes.”

If

she had talked to some of those monitoring groups, readers would have gotten a

very different picture. The monitoring project Airwars, for example, says that

at least 575 civilians have been killed in well-reported incidents connected to

confirmed US or US-allied airstrikes from August 2014 through August 2015.

With nearly 5,000 airstrikes conducted by the US and its allies in the

first 11 months of the bombing campaign, this suggests that for every 10 air

raids Yip Yip and Bones carry out, roughly one civilian is killed.

Cooper is

right about one thing: That sure doesn’t sound like Top Gun.

Jim Naureckas is the editor of FAIR.org.

You can send a message to the New York Times at letters@nytimes.com,

or write to public editor Margaret Sullivan at public@nytimes.com (Twitter:@NYTimes

or @Sulliview).

Please remember that respectful communication is the most effective.

Donations

can be sent to the Baltimore Nonviolence Center, 325 E. 25th St., Baltimore, MD

21218. Ph: 410-366-1637; Email: mobuszewski [at] verizon.net. Go to http://baltimorenonviolencecenter.blogspot.com/

"The

master class has always declared the wars; the subject class has always fought

the battles. The master class has had all to gain and nothing to lose, while

the subject class has had nothing to gain and everything to lose--especially

their lives." Eugene Victor Debs

No comments:

Post a Comment